4 Future-Proof Organizational Models Beyond Hierarchy And Bureaucracy

In a previous post we introduced the concept of “middle-manager-less-organizations” (MMLOs for short). These companies run their businesses successfully without a middle management layer. Large and small, they point the way forward for organizations wanting to go beyond the traditional hierarchical/bureaucratic model, a way of organizing that is increasingly outdated and has deep roots in ‘industrial age thinking’.

But there is not only one model that companies use to avoid the traps of hierarchy and bureaucracy. When we look at how MMLOs are organized, we see four distinct approaches. Each attempts to minimize hierarchy and bureaucracy. And each seems to have roots in different places (albeit not in the industrial age!).

We have identified a ‘European Model’, an ‘American model’, an ‘Asian Model’ and a ‘Digital Model’. In this post we explore each in more detail.

But first, let’s review three things;

- Why the machine view of the organization is outdated

- What ‘social networks’ are

- Why two ‘problems of organizing’ are important in MMLOs

Organizations as man-made machinery

First, to truly understand how MMLOs organize themselves, we need to move away from our habit of seeing organizations as ‘man-made machinery’. This misunderstanding is grounded in the beliefs that (a) a company is best organized via hierarchy, and (b) its workings are best controlled by a bureaucracy.

This mechanical concept of organizations owes a lot to the successes of the industrial age. But these hierarchies/bureaucracies often led to impersonal organizations built on rules, procedures and controls, which then often took on a life of their own. The result, today, is a world of work with disengaged employees: a world where people do little more than is required of them.

Luckily, there are organizations that move with the times. These pioneers have developed alternatives to out-of-date hierarchies and the sclerosis of bureaucracy. These MMLOs are achieving impressive results in both employee satisfaction and business outcomes. They do not rely on a mechanical view of the organization. They see it as a ‘social network’; a network with a dynamic, self-organizing character, guided by the interaction of its underlying building blocks.

MMLOs as social networks

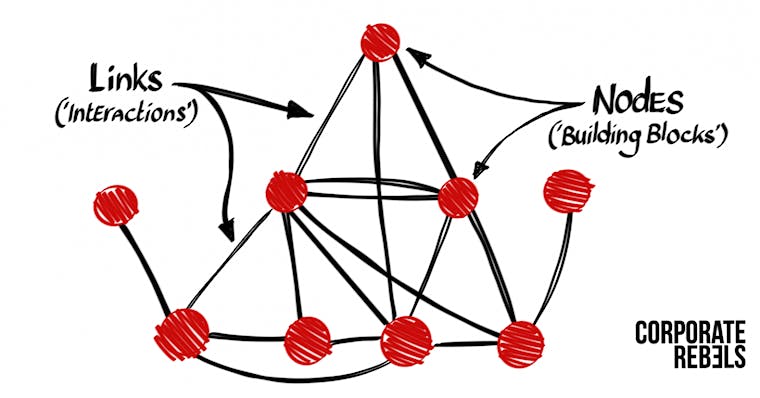

To understand MMLOs, it helps to think about them as networks like those in transportation (e.g. the metro) and information (e.g. the internet). These consist of “nodes” that are the building blocks of the network (i.e. metro stations, or computers). We also know the “nodes” are connected by links that manage interactions between them.

A network gives us an image of how objects can connect and interact with each other. It is not difficult to see this representing a ‘social network’--a collection of individuals, or groups of individuals, that interact with each other.

We have visited MMLOs around the globe and observed some differences in these connections. Put another way, we found differences in how individuals connect and interact with each other. Specifically, we saw clear differences in how MMLOs solved two important problems of organizing.

The problems of organizing

Before we describe the differences in solving these two problems of organizing, we should recap what these ‘problems of organizing’ are. In the previous post we argued that every organization needs to solve 3 problems as shown in the picture above:

- The problem of organizing direction

- The problem of organizing vertically

- The problem of organizing horizontally

The latter two are particularly interesting. Let’s explore them in more detail.

‘Organizing vertically’ includes the challenge of separating the objectives of the organization into tasks and roles. Then there is the issue of mapping these tasks and roles to employees. In traditional organizations, this ‘vertical problem’ is often solved by introducing a hierarchy, and a middle management layer that allocates tasks and roles to employees.

‘Organizing horizontally’ includes the challenge of giving employees enough information to coordinate efficiently with peers. In traditional organizations, this ‘horizontal problem’ tends to be solved by introducing a bureaucracy, with associated rules and procedures to guide employees.

The two problems of organizing of MMLOs

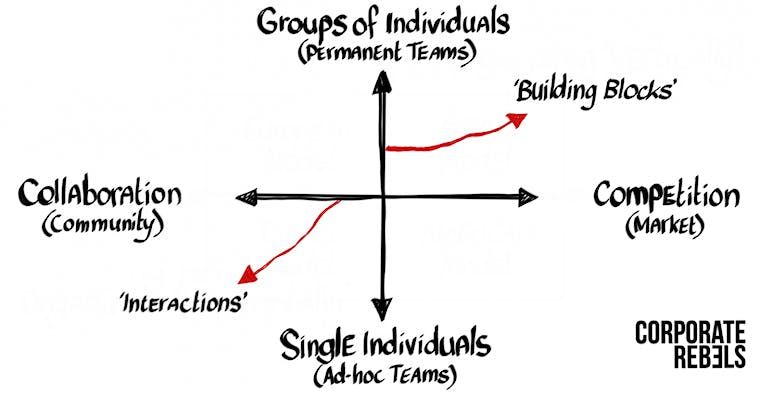

By combining a ‘social network view’ with the vertical and horizontal problems of organizing we create a matrix as above. In this matrix, the vertical arrow represents the ‘vertical problem’ and, likewise, the horizontal arrow the ‘horizontal problem’.

From our observations of MMLOs, large and small, we conclude that both the vertical and horizontal problems can be solved without the need for a hierarchy or stifling bureaucracy. There are effective alternatives. At the MMLOs we visited, we saw different ways to solve these problems.

We group these efforts into two distinct sets of solutions for both the ‘vertical’ and the ‘horizontal problem’. We draw these solutions below.

In this matrix, the opposite ends of the arrows represent two sets of solutions. Roughly speaking, the ‘vertical problem’ can be approached by designing the organization around either single individuals or groups of individuals. The ‘horizontal problem’ can be approached by promoting either collaborative or competitive interactions. As you would expect, these different approaches lead to different dynamics.

Ad-hoc Teams vs. Permanent Teams

As we argued in a previous post, MMLOs typically solve the ‘vertical problem’ by breaking the organization into small ‘building blocks’ to create a modular yet flexible structure. If we use a social network metaphor, we can think about ‘nodes’ as the fundamental building blocks of the social network. In MMLOs these ‘nodes’ can be individuals or teams. This gives rise to two scenarios.

On the one hand, the first ‘vertical scenario’ regards individuals as the fundamental building blocks of the organization. In this scenario, groups of competitive, decision-making people self-organize into ad-hoc teams without the need for an “invisible hand” or central controller (like a middle manager). This means the entire organization is structured around individuals who are part of one or more ad-hoc teams. These ad-hoc teams emerge and dissolve organically via the collective actions of all individuals in the organization.

On the other hand, the second ‘vertical scenario’ regards groups as the fundamental building blocks of the organization. In this scenario, people self-organize into permanent teams, with individuals always being part of just one permanent team. This means the entire organization is structured around relatively stable teams. New teams emerge when a group of entrepreneurial individuals desire it.

Community vs. Internal Market

In the same post we argued that MMLOs (typically) solve the ‘horizontal problem’ by introducing a set of ‘rules of the game’ to act as guidelines for how the ‘building blocks’ should interact with each other. The desired interactions can be focused on collaboration or on competition. Again, this creates two scenarios.

On the one hand, one ‘horizontal scenario’ promotes collaborative interactions between ‘building blocks’ to emphasize a sense of community. In this scenario, organizations create a sense of belonging by adopting a mission people are motivated to contribute to. Most often, organizations with this scenario avoid market-like incentive mechanisms.

On the other hand, another ‘horizontal scenario’ promotes competitive interactions between the ‘building blocks’--to create an internal market system. In this scenario, organizations foster an environment where people compete for resources based on their judgement of what they want to contribute to. Organizations that opt for this second scenario most often put a financial value on the contributions made, thereby creating market-like incentives.

The 4 organization models of the future

These four different organization dynamics give rise to four scenarios (or ‘models’) that enable management of organizations without a middle management layer. All these models are based on ‘network of teams’ structures that emphasizes the dynamic, self-organizing nature and interactions of the underlying building blocks, whether these be single individuals or permanent teams. Let’s explore them one by one.

The European Model

First, the European Model. This is based on a set of European-based companies that include the Spanish NER Group and the (former) French FAVI. The best example is probably the Dutch healthcare organization, Buurtzorg.

In this scenario, organizations divide into permanent self-organizing teams, often with roots in local communities. How the teams are divided differs for each organization. They can be based on regions (like Buurtzorg), products/services (like NER Group), clients (like FAVI), projects or a combination of these options. Commonly, these permanent, self-organizing teams are kept small. Think ~10 to 15 people.

All permanent, self-organizing teams in this scenario interact in a collaborative way. They share the aim to form one big community with a clear purpose. In Buurtzorg’s case, this is “to deliver good quality care”, with monetary rewards for individuals being tied to the performance of the organization as a whole and not to the performance of local teams. There are no individual performance bonuses.

In this model there is little sense of competition between teams, as each is dedicated to its own region, product, service, client or project. At Buurtzorg, for example, teams are geographically defined and strongly embedded in local communities. They are dedicated to serving clients in their own ‘region’. To stimulate collaboration, Buurtzorg introduced a set of rules (that they regard as necessary but minimal bureaucracy) that discourages teams from competing with each other. For example, teams cannot ‘steal’ clients from other ‘regions’. Instead, all are encouraged to collaborate to find the best solutions possible for all clients.

The Asian Model

Second, the Asian Model. During our travels we visited only one company that exemplified this model—the Chinese white-goods giant, Haier.

In this scenario, organizations divide into permanent self-organizing teams that compete for resources in an internal marketplace. As in the European scenario, teams can be based on regions, products, services, clients, projects, or a combination. Teams in the Asian scenario are also small. This creates an ecosystem of start-ups. All conduct business with each other as they wish. For example, at Haier, there are >4,000 mini companies.

All self-organizing teams in this scenario act as independent mini companies. They make transactions and contracts with each other as if they were in an external market. Because of this, teams interact in a more competitive manner. Monetary rewards for individuals are more closely tied to the performance of their team.

How does this work in real life? Imagine you are a member of such a mini company. And let’s say your team is delivering HR services to other mini companies in the network. But you don’t only deliver services to other teams. You need to sell them, and they need to buy from you. If you don’t sell enough, your team can go bankrupt, and you and teammates will lose your jobs.

Plus, your team needs to deliver competitive services because yours is not the only team offering HR services. Several teams in the network are permitted to offer HR services. This creates a competitive environment. Every team needs to add enough value to internal or external customers to survive.

The American Model

Third, the American Model. This is based on American-based companies like W.L. Gore, Morning Star and Valve.

Organizations in this scenario rely on individuals as the building blocks of the network. In this model, it is not teams that make commitments, but individuals who make commitments to each other (and the organization). Sometimes, as at Morning Star, these commitments are actual contracts.

The competitive nature of this scenario comes from the fact that all individuals have the same global information, and all are competing for limited resources. This creates an environment where ad-hoc teams can emerge and dissolve constantly, decided by a market mechanism based on individual commitments.

For example, at WL Gore there are many ad-hoc teams of ~8 to 10 people focused on the opportunities around individual business commitments, whether that is a product, a service or some other initiative. This means many individual commitments are a ‘slice of the cake’ that gets delivered in a whole package – be it a product, service or another initiative.

However, in this scenario there is a similar competitive mechanism to that of the Asian Model. lmagine you are (still) delivering HR services. In the American Model you deliver this service not as a permanent team, but as an individual to others in the organization. Once again, you can’t force your HR services upon others. Individuals need to request them from you. This is often not straightforward as there are other individuals in the organization competing for the same HR commitments. This means every individual needs to add enough value or they will not be able to make enough commitments.

The compensation mechanism in the American scenario is (mostly) based on commitments individuals make, with individual rewards closely tied to the performance of that individual. At WL Gore, compensation is decided by a panel of peers that judges if individuals have done a good job or not—and ranks this contribution. This provides a set of data that places an individual is at the top of the list in the eyes of their peers, or at the bottom. Compensation is mediated via this list. If you are ranked highly, you will get higher pay.

The Digital Model

Lastly, the Digital Model. This is based on a group of online organizations like Wikipedia, Linux, (former) GitHub and other open source communities that encourage collaboration.

As in the American Model, the organizations in this scenario rely on individual contributions. However, there are no monetary rewards for contributions made to the open source communities. In fact, the contributions are mostly voluntary, and made by individuals who identify with the communities they are part of.

Most often, anyone with an account can add value to the open source community they are part of. In this way, the commitments of single individuals create an environment where ad-hoc teams emerge and dissolve constantly, around projects. This leads to a dynamic that is driven by individuals collaborating to add value.

For example, Wikipedia is the collaborative effort of largely anonymous volunteers who write and add value without pay. Anyone with internet access can make changes to Wikipedia articles, and anyone can contribute to the organization. However, there are policies and guidelines that guide this process. But there is no formal requirement to be familiar with them before contributing.

MMLO hybrids

The world is not black and white. Nore are companies are entirely collaborative, or solely competitive. Some use both kinds of interactions to link the building blocks of their organization. However, usually, one approach will dominate the other. What will dominate is either the financial value added to the organization, or the contribution made to the purpose of the larger community.

But, sure, both approaches can be combined in a hybrid approach. For example, the European Model emphasizes collaborative interactions between individuals. But in reality, there is also some competition between the permanent teams to perform better than others.

Similarly, with the American Model. While this model emphasizes competitive interactions between individuals, people in this model must also collaborate with others. The ad-hoc teams share the responsibility for end results collectively. In the end, the individual commitment of most people in this model is part of the commitment of the team.

In reality, we cannot place any organization in just one box or the other. The model is better seen as a continuum as in the graph above, with all MMLOs being hybrids that either emphasize a more collaborative environment, or a more competitive environment. This emphasis determines the pattern we observe from the outside.

The same is true for the fundamental building blocks. No MMLO is exclusively built on permanent teams, or exclusively on ad-hoc teams. Once again, this looks more like a continuum where the majority counts as the observable pattern for outsiders.

Sets of solutions

Taking that into account we dare to argue that MMLOs show the following shifts in their sets of solutions compared to more traditional firms:

- The solution to the 'directive' problem shifts from a focus on short-term maximizing shareholder value towards a focus on long-term objectives that are guided by optimizing the value for all stakeholders.

- The solution to the 'vertical' problem shifts from a focus on hierarchical organizational structures towards a focus on networks structured around relatively simple building blocks of (permanent or ad-hoc) self-organizing teams.

- The solution to the 'horizontal' problem shifts from a focus on top-down bureaucratic guided interactions towards a focus on voluntary collaborative or competitive interactions between these building blocks of the network.

Your questions and thoughts

Before we invite you to share your thoughts and questions, let’s clarify a few additional points;

First, as briefly introduced above, the matrix and its respective models are abstractions of reality. We do not have the ambition, nor the ability, to capture all the mysteries of organizational reality. The matrix and its models do, however, capture patterns observed while visiting MMLOs around the globe.

Second, the geographical location of an organization doesn’t necessarily determine which model fits best. In other words, not all European companies will fit the ‘European Model’, nor will all American companies fit the ‘American Model’. The names of the models reflect where their roots are based.

Third, there might be MMLOs that do not fit any of these models. For example, where do we place organizations operating with Sociocracy or Holacracy in this matrix?

Fourth, organizations are not stuck in one model but can migrate from one to another as they desire. Take, for example, Zappos. This American retailer was once famous for its ‘Holacracy at scale’ experiment. But it is now introducing internal market-like contracting between its teams, which moves them toward the Asian Model (as an American company – see the second point). On the other hand, Haier, the poster child of the Asian Model, is now experimenting with more collaborative practices between its teams, and therefore moves gradually toward the European Model.

Fifth, there are inspiring organizations that are radically decentralized but do not conceptually qualify as MMLOs. For example, the Swedish Handelsbanken would perfectly fit the European Model but they do not operate completely without middle-management. Why are they interesting then? Because the >15.000 employees of the bank are structured around >750 small permanent teams that autonomously run their own local banks. These self-organizing teams are strongly rooted in the local communities and take all important decisions locally. Because of this local focus there is a minimum level of competition between the permanent teams as all teams only serve their own clients.

Sixth, obviously there are also more traditional shaped organizations that move (mostly partially) towards one of the MMLO models. For example, the Chinese Tencent is currently experimenting with the introduction of the Asian Model and has recently restructured 8 large divisions into 20+ small permanent teams that compete on an internal market place for organisational resources, with the bonuses of the self-organizing teams being tightly connected to the profit each permanent team manage to achieve.

And last, but not least, we do not necessarily value, or promote, one model above the others. There is merit in all four. The key is how well a model fits the people in the organization.

Despite all the above, we do think there is value in sharing our ideas with anyone who desires to transform their organization to a more humane and future-proof one.

What do you think?

What questions and thoughts do you have about the matrix and its elements?

Some of the concepts in this post are developed during my ongoing academic adventures at the VU University Amsterdam. Many thanks to my academic co-workers;

- Dr. Nicolas Chevrollier (Nyenrode Business School),

- Prof. Dr. Svetlana Khapova (VU University Amsterdam),

- Dr. Brian Tjemkes (VU University Amsterdam).