How To Organize A Large Company Without Middle Management

In early 2018 I took on a new challenge. After two years in the popular management world I decided to take a leap into academic life. I started a part-time PhD program in Business at the VU University Amsterdam. Since then I have researched how large organizations (with thousands of employees) can scale and organize without the need for middle management. It’s time to share what we’ve learned.

Warning: This note has turned out to be a long read. As the mathematician Pascal once famously wrote; "I have made this longer than usual because I haven’t had time to make it shorter". I'm sorry about that.

The phenomenon

After reading the academic literature on the topic we discovered two main things:

- The literature on 'companies organizing without middle management' has been of interest to academics for years,

- And, the current debate revolves predominantly around a limited amount of real-life cases.

Namely:

- GitHub (American IT company with ~900 employees. Owned by Microsoft.)

- Valve (American IT company with ~400 employees. Owned by founder Gabe Newell.)

- Morning Star (American food company with ~600 employees. Owned by founder Chris Rufer.)

- Zappos (American online retailer with ~1,500 employees. Owned by Amazon.)

These four are often mentioned as having 'departed radically from formal hierarchies' and having 'eliminated the role of middle management completely'.

They also have been labeled in different ways over the years:

- 'Non-hierarchical organizations' (by Herbst in 1976),

- 'Boss-less organizations' (by Puranam et al. in 2014),

- 'Self-managing organizations' (by Lee & Edmondson in 2015).

The academic status quo

We have visited many examples of this kind of organization. And there are two easily observed issues with the academic status quo:

The first is a minor one. We think that the proposed names for the phenomenon of 'companies organizing without middle management' are incorrect. This is because all the companies studied still have a top management team (CEO, founder and/or owner) in place that enjoy the ultimate decision-making authority. This means these companies are not without hierarchy, nor bosses, and therefore are not completely self-managed.

This also means the proposed names don’t capture the specific phenomenon we observe. Accordingly, we propose a new name for this phenomenon: 'middle managerless organizations', or MMLOs for short.

The second issue is more important. The four cases above are not only exclusively American but also relatively small companies (up to 1,500 employees). This 'smallness issue' leaves room for skeptics to question whether MMLOs can be scaled to, say, organizations of >10,000 employees.

Indeed, many academics would argue that all start-ups initially look like MMLOs but tend to switch to managerial hierarchies (with the introduction of middle management) as they grow and increase coordination, control, and communication. Accordingly, many doubt the feasibility of MMLOs at scale.

This second issue is the one I want to address in this post.

Three inspirational cases

Despite the skepticism of some scholars, and after visiting progressive workplaces for our Bucket List, we are certain large organizations can organize without the need for a middle management layer.

Indeed, we have seen this with our own eyes. Three inspirational cases show you can organize thousands of employees without the need for middle management. We select these cases from three continents (America, Asia, Europe) to ensure a worldwide view. They are:

- W.L. Gore (American manufacturer with ~10,000 employees. Owned by founders' family and employees.)

- Buurtzorg (Dutch not-for-profit, healthcare organization with ~15.000 employees.)

- Haier (Chinese white-goods manufacturer with ~75.000 employees. Collectively owned.)

The 5 problems of organizing

Before describing 'how' Gore, Buurtzorg, and Haier organize without middle management, we first need to agree on what exactly we mean by 'organizing'.

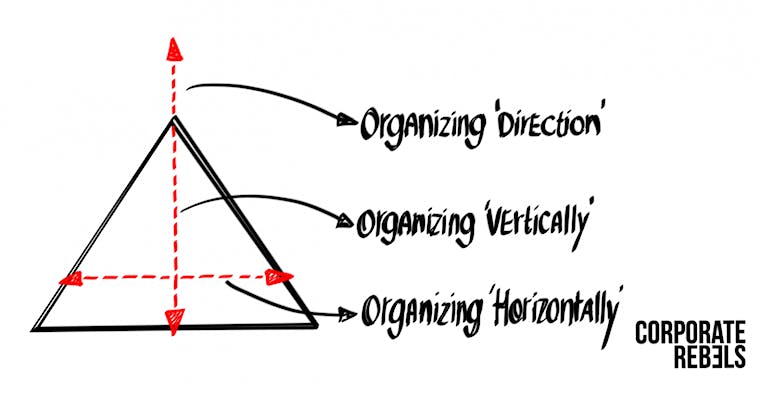

For this, we look at the work of scholars like Lawrence & Lorsch, Mintzberg, Burton & Obel, Birkinshaw, Puranam, Lee & Edmondson. Informed by these scholars, we argue that any functioning company (of two or more employees) should solve three intertwined problems:

- Strategy (organizing the direction of the company)

- Division of Labor (organizing 'vertically' in the company)

- Integration of Effort (organizing 'horizontally' across the company)

The latter two can be divided into four sub-problems. 'Division of Labor' can be divided into 'Organizational Structure' and 'Task Allocation'. 'Integration of Effort’ can be divided into 'Coordination' and 'Motivation'.

This leaves 5 fundamental problems of organizing that any company, by definition, must solve:

1. Strategy

This is the problem of defining the company's strategic direction and related objectives. This is traditionally done by a top management team that defines short-term (mostly monetary) goals.

2. Organizational Structure

This is the problem of separating the objectives set by top management into tasks and roles. This is traditionally done by the introduction of a hierarchy (often with functional departments).

3. Task Allocation

This is the problem of mapping tasks and roles to employees. This is traditionally done by middle management who allocate tasks and roles to employees.

4. Coordination

This is the problem of providing employees with the information they need to coordinate actions with peers. This is traditionally done by a middle management layer via rules and formalized procedures to guide and control employees.

5. Motivation

This is the problem of monitoring the performance of employees and distributing rewards for the tasks they have performed. This is traditionally done by a middle management layer that monitors employee performance and decides the allocation of rewards.

Looking in this light, 'organizing' can be regarded as a set of solutions to these five problems. It also gives us five dimensions with which to analyze and compare solutions developed by different kinds of organizations.

Large 'Middle Managerless Organizations'

Now that we have defined with what we mean by 'organizing', we move on to our next question. How do large MMLOs solve these five fundamental problems of organizing?

To answer, we need to go back to the three cases: W.L. Gore, Buurtzorg, and Haier.

We analyze and compare solutions developed by these three companies on the five dimensions we introduced above and explain how large companies can successfully organize themselves without middle management.

1. Strategy

Strategy in large MMLOs seems predominantly the domain of small, top management teams who define, promote, and guard long-term organization-wide objectives and culture norms.

Small top-management teams

All three companies have small top-management teams with formal authority and responsibility for overall company performance. These teams ultimately decide about employment contracts in the company (often on the recommendation of other employees).

At W.L. Gore this is the so-called Enterprise Leadership Team which consists of only four people. At Buurtzorg there are only two directors, both of whom are founders of the organization. And at Haier, a small top-management team is headed by founder and CEO Zhang Ruimin. Apart from the members of these top management teams, all others in the three companies are employees with no assigned formal authority.

Long term objectives

The strategy at all three companies is defined by long-term objectives. W.L. Gore's objective has not changed since 1958 when founder Bill Gore stated their mission was "to make money and have fun doing so". Buurtzorg’s mission is “to deliver good quality care”. This hasn't changed since the founders started—to simplify and improve the Dutch healthcare system. Haier’s mission is “To become the world leader in smart appliances”.

These long-term objectives guide all employees in the judgments they make about the commitments they make for themselves and their colleagues. By highlighting a desired future, top-management teams create a beacon for employees: a beacon to contribute to in a freer manner. Strategy is founded on a single mission rather than a lengthy and complicated description.

Culture norms

Strategy at all three companies is guided by internal norms and traditions - the "how we do things here" - that fill much of the void left by the absence of hierarchical management. Those cultural norms are simple rules that ensure all decisions are aligned with company strategy and priorities.

For example, employees at W.L. Gore are expected to live by four explicit, widely shared, guiding principles. These are freedom, fairness, commitment, and waterline. At Haier and Buurtzorg, there are widely shared cultural norms as well. However, these are not documented but transmitted informally by members of the top-management teams and the more experienced employees.

2. Organizational Structure

The organization structure of large organizations without middle management is based on a 'network of teams' structure. Employees self-organize into teams around tasks with end-to-end responsibility. New self-organizing teams are initiated by groups of entrepreneurial employees.

Modular organizational structure

The structure of all three companies is flexible and modular and consists of self-organizing teams. Employees enjoy the freedom to organize into teams to perform tasks and activities. In teams, employees can organize however they think is best for themselves and their customers. These teams have far-reaching decision-making power but are also accountable for their performance.

Haier has pushed this concept of radical decentralization to the extreme. Their self-organizing teams are run as independent companies (some even as separate legal entities) with employees sharing ownership, and being responsible for all kinds of decisions like contracting, recruitment, and budgeting.

Small self-organizing teams

The self-organizing teams in these companies are often small. They take one of two shapes: ad-hoc teams (W.L. Gore) and permanent teams (Haier & Buurtzorg). At W.L. Gore ad-hoc teams emerge around interactions and commitments between groups of employees. All employees can team with others to get their jobs done, and employees can be in multiple teams. Thus, W.L. Gore’s numerous small, ad-hoc teams emerge as new tasks are initiated, and dissolve once the task is done.

On the other hand, Buurtzorg organizes around >1,000 permanent, self-organizing teams, with employees being in only one team. The teams are geographically defined, each choosing their 'territory'. When a team grows beyond 12, a rule says it must split to maintain its small-scale team structure.

Similarly, Haier has split the company into >4,000 permanent teams, internally referred to as "microenterprises". The size of teams varies quite a bit, but most consist of ~10 to 15 employees. All are connected to a dedicated online platform, with platforms grouping about 50 teams.

Emerging teams

New teams at all three companies emerge in an organic manner, initiated by entrepreneurial employees. New teams only start when a group of employees gets excited about pursuing an opportunity or solving a specific problem. A new team is only launched when a group of employees is convinced that there is a demand for it. Thus, new teams emerge and grow in a free-flowing, bottom-up fashion.

At W.L. Gore new teams emerge only when at least two employees are convinced there is a real demand for the proposed idea. When the new idea needs serious investment, the employees must first pitch their idea to a committee of peers in order to get resources.

A similar thing happens at Buurtzorg, as the organization doesn't set up new teams. It relies on new teams emerging organically when a group of entrepreneurial employees sees the need for services in an area not yet served. However, new teams can only be initiated when there are at least four potential team members willing to join.

At Haier, new teams are typically initiated by groups of entrepreneurial staff via their online platforms. Employees are encouraged to share ideas online and invite others to join them in pursuing an entrepreneurial adventure. A new team only emerges when there is a minimum of three individuals willing to start the new 'microenterprise'. Like W.L. Gore, when launching investments are needed, new teams pitch their ideas to a committee of peers to request resources.

However, top management teams hold an important role in this regard. They hold the ultimate authority to terminate or dissolve teams that are, for example, not performing up to organization standards in terms of productivity and/or client satisfaction. They also approve, or not, additional resources to teams that move beyond the existing company boundaries; for example, teams that want to explore new products, services or geographical areas.

3. Task Allocation

The process of task allocation in organizations without middle management seems defined by the nature of the work the teams need to do. Employees in the teams allocate tasks and roles based on voluntary, self-selected commitments and consensus decision-making. Employees emerge to fill natural leadership roles.

Customer-facing and support teams

The task allocation process in all three companies is influenced by the work team members must execute daily. A rough distinction can be made between two kinds of teams; customer-facing teams (in direct contact with customers) and support teams that enable the customer-facing teams to deliver products and services in the best possible way.

At Buurtzorg, most teams are customer-facing and offer services to customers. They also have a small number of support teams at headquarters for tasks related to finance, legal, and administration. Note that no group holds any formal authority over the others.

By way of contrast, most of Haier’s teams are support teams. Only a small number are in direct contact with end-users of their products. Most offer services for back-office functions like HR, legal, and administration, or deliver services in designing, manufacturing, and distributing Haier products. Any team at Haier can be dissolved or go bankrupt (most are separate legal entities) when they do not provide a competitive service or product – much like any start-up would in the marketplace.

Self-selected task commitments

In all three companies, employees allocate tasks and roles within their own teams. This is based on voluntary, self-selected task commitments and consensus decision-making. These commitments define decision-making roles in the team and assign accountability to the employees who take on those commitments.

At W.L. Gore, employees commit as individuals to the tasks and activities they wish to perform. These are called ‘self-commitments’, which means employees can join and leave teams based on their own needs and interests. However, once employees make commitments, they are expected not to break them, unless due to exceptional circumstances. And if an employee feels they are making a commitment that could threaten the organization’s survival, they are expected to review this with more experienced employees before they commence.

At Buurtzorg, all self-organizing teams must fulfill 7 roles. One of these is the main one (being a nurse) which must be shared by every member. All other roles (like administration, finance, collaboration, leadership, and HR) must be distributed amongst team members. They do this in a way they think makes good use of the skills of all members. All major team decisions are by informal consensus. Team members collectively share responsibility for these commitments and decisions.

Likewise, at Haier, team members enjoy formal authority over their internal task allocation process. This means that teams define their own working relations and decide how to allocate tasks and roles within their teams. Teams make collective commitments to other teams in the form of contracts which often take place on their online platforms. Any contract can be renegotiated after a year.

Natural leadership roles

All three companies focus on natural leadership roles. That is, roles are often allocated to employees best positioned to do them. Again, there are roughly two kinds of leadership roles: those within a team and those across several teams. Note that none of these roles include any responsibility for managing other employees, nor do they have any formal authority over others.

At W.L. Gore there are many leadership roles, with employees selecting leaders amongst peers based on credibility and their ability to attract followers. It is expected employees with the right expertise take on relevant decision-making responsibilities. This is internally referred to as ‘knowledge-based decision-making’. These leadership roles can take many different forms. For example, there are team leaders, business leaders, and plant leaders. There is also a group of self-selected leaders referred to as sponsors. Sponsors offer feedback on performance, guidance in personal development, participation in the compensation process, and how to identify new ways of contributing.

A similar kind of leader can be found at Buurtzorg where all teams select their own informal leaders into ‘mentor’ roles. These mentors take care of things like onboarding and coaching. A small group is referred to as coaches. Each supports a group of teams with things like problem-solving, network building, starting up new teams, and sharing best practices. These coaches are dedicated to a certain region and focus on facilitating solutions rather than providing them. This also means that leaders in Buurtzorg have no formal authority over other employees.

At Haier, teams formally select their own leaders who act as CEOs of microenterprises. These leaders are chosen by a consensus of team members. They can be replaced if the team is underperforming. These leaders act much like leaders of a start-up within a bigger company, and do not need any approval from top management for decision-making. There is also a group referred to as platform leaders. They support and promote collaboration between different teams on the same platform. However, once again, these leaders do not hold any formal authority over employees or teams.

4. Coordination

Coordination of activities and tasks in large organizations without middle management happens mostly via direct person-to-person interaction and digital tools. Top management has established clear “rules of the game” to coordinate all activities and tasks as efficiently as possible.

Direct person-to-person interaction

In all three companies, any employee can talk to anyone, and no one tells another what to do. This means that all employees can interact freely with every other employee in the company with no intermediary (like a middle manager) necessary to coordinate this formally or informally. All three companies keep teams small on purpose, so team members can coordinate informally and in an efficient manner. It is for this reason that employees are expected to meet face-to-face regularly. Not surprisingly, perhaps, employees in natural leadership roles play an important part in the coordination process.

Since every employee at W.L. Gore needs to find and make their own task commitments, it is important to build an extensive personal network. Employees bear the responsibility to do this. This is why most new employees at W.L. Gore spend their first few months building relationships and networks across the company, by working in several teams.

At Buurtzorg, team members meet at least one day every week in the office to coordinate work. The organization runs regular conferences and regional meetings to bring employees from different teams together, so they can get to know colleagues from other teams and learn from each other. In addition, teams at Buurtzorg are strongly embedded in the local community. Therefore, they coordinate their work locally with other stakeholders (like clients, doctors, and families of clients).

Digital tools

All three companies have developed digital tools to facilitate coordination, especially for employees who are not physically close. This promotes high levels of connectivity throughout the company. This helps employees share knowledge, experience, and ideas. It also gives employees tools to coordinate and communicate with other stakeholders, like clients and suppliers. They exchange information to develop joint solutions to problems.

At Buurtzorg, a digital tool called BuurtzorgWeb aims to simplify the execution of day-to-day work activities, allowing employees to concentrate on face-to-face interaction with clients. It provides increased levels of transparency about all kinds of real-time information related to team-based and individual performance, client information, organizational strategy, and financials. At W.L. Gore, for example, the top management team shares financial results through digital tools with all employees, monthly.

At Haier, digital tools are used extensively to coordinate with customers and other partners. They use an online platform, called Haier Open Partnership Ecosystem, to communicate and collaborate with stakeholders. These are also used to get customer feedback on the design, development, production and use of their products. In this way, Haier uses technology to engage with thousands of people in collaborative interactions and information-sharing in a cost-efficient manner.

Rules of the game

Although employees at all three companies have far-reaching decision-making authority to coordinate work with others, they still need to observe organizational ‘rules of the game’. These are often established by the top management team. All are expected to respect and enforce the rules of the game—to coordinate work efficiently, to resolve disputes fairly, and to prevent new activities that would make the company less efficient. These rules of the game provide day-to-day guidance for teams to collaborate efficiently while trying not to compromise the independence of the teams.

At W.L. Gore, for example, there is a rule that restricts the size of any facility to a maximum of 300 employees. At Buurtzorg, there are rules that restrict teams from becoming larger than 12 employees. Plus, teams must meet an internal productivity target of 60%, meaning that 60% of their hours must be billable. Moreover, rental costs of accommodation cannot exceed 1% of team turnover, and 3% of an employee’s time must be devoted to training and education.

At Haier, there is an extensive set of rules related to coordination between microenterprises. These cover internal contracting, performance standards, and target setting. For example, all teams should set themselves ambitious growth and profitability targets, based on global market growth rates. These targets must be externally benchmarked and broken down into quarterly, monthly, and even weekly goals for each individual and team.

5. Motivation

Beyond being intrinsically motivated to perform, motivation in large MMLOs is the domain of employees via transparent peer rankings of performance. Based on these, rewards are distributed for individual short-term compensation (like salary) and long-term compensation (like bonuses and dividends).

Transparent performance rankings

In all three companies, some form of transparent peer ranking is used to assess the performance of peers. The performance of anyone in the organization is centrally monitored on a few metrics with real-time performance of employees or teams being visible to all in the organization. This creates a reputation system of peer ranking that allows for self-monitoring and peer-control. These systems are also used to encourage internal collaboration and competition based on performance and reputation.

W.L. Gore uses a peer-ranking system to assess individual performance, while Buurtzorg’s and Haier’s peer-ranking systems are based on team performance. At Buurtzorg and Haier, all teams are measured on a few key metrics, often related to productivity, profitability, and customer satisfaction. This enables teams to compare themselves with others in a fair and straightforward way.

Individual short-term compensation

At W.L. Gore and Haier, short-term individual rewards, like salaries, are based on transparent performance rankings, to ensure internal competitiveness and fairness. Both companies make sure that rewards are regularly benchmarked against functions and roles at other companies to ensure external competitiveness.

At W.L. Gore the internal performance peer-ranking system is used to determine the level of individual salaries, with all employees being peer-ranked about twice a year. The salary of every employee is decided and assigned by a committee of colleagues who are often from the same location. At Haier, short-term compensation is rather defined by the performance of the team as most microenterprises are legally independent entities with employees holding shares. This means employees at Haier are rewarded more like entrepreneurs rather than employees.

At Buurtzorg, it is a different story, as all employees at Buurtzorg are paid a salary under a union agreement according to education level, with a standard annual increase based on the number of years working for the organization. Employees of Buurtzorg seem to be more motivated by the organization’s ideology rather than by financial gain. This is also visible in that performance peer-ranking systems are solely for intrinsic, short-term rewards (like pride and status), and the organization does not distribute monetary incentives based on these rankings.

Collective long-term compensation

Next to individual rewards, the three companies distribute long-term collective rewards to all employees depending on whether goals and overall profitability targets are reached. These collective rewards are based on profit-sharing, distribution of dividends, or employee ownership plans. Buurtzorg has the simplest practice. Depending on the profitability of the organization an annual bonus is distributed collectively to all employees in an equal manner.

At W.L. Gore profit-sharing typically takes place twice a year. The share of the profits that each employee receives is relative to their salary and years of service. Besides profit-sharing, each employee of W.L. Gore becomes a stockholder after one year of service. For each employee, W.L. Gore purchases stock equivalent to 12% of salary and contributes this to individual accounts. Employees get ownership of their accounts after three years of service.

At Haier, ownership of the microenterprises is shared between the company and employees who are part of that team. The members of the team can collectively hold a maximum of 30% stake in their own microenterprise. In some cases, when extensive capital is needed, outside investors share part of the ownership. Via this practice, long-term compensation at Haier is tied to the number of shares an employee owns and the profit of the team he or she is part of.

Conclusion

Having analyzed and compared the solutions to the five problems of organizing that the three large MMLOs have implemented, we conclude that they show remarkable similarities in how they approach strategy, the division of labor, and the integration of effort.

However, there are also two notable differences to observe. The first difference is related to the division of labor (organizing 'horizontally'). On the one hand, some companies do well by dividing the company into thousands of dynamic ad-hoc and temporary teams, as W.L. Gore is structured. On the other, companies like Buurtzorg and Haier depart from this idea and swear by dividing the company into hundreds or thousands of stable and permanent teams.

The second difference is related to the integration of effort (organizing 'vertically'). On the one hand, W.L. Gore and Haier have clearly introduced certain market mechanisms to streamline the coordination and motivation of all teams and employees. On the other hand, Buurtzorg stays apart from market mechanisms and relies much more on the intrinsic motivation of employees to establish a culture of collaboration between all teams and employees.

But how this exactly works in detail is something I will explain in a future blog post. For now, I'm curious what your thoughts are about this concept of MMLOs. Please drop them below.

Acknowledgment

Many thanks to the co-workers in my academic adventures;

- Dr. Nicolas Chevrollier (Assistant Professor at Nyenrode Business School),

- Prof. Dr. Svetlana Khapova (Professor at VU University Amsterdam),

- Dr. Brian Tjemkes (Associate Professor at VU University Amsterdam),

- Ken Everett (Adjunct Professor at Chinese University of Hong Kong).