Mass Incompetency In Business: The Way We Promote People Is Dead Wrong

In 1969, Laurence J. Peter described an interesting organizational phenomenon. The phenomenon came to be known as “The Peter Principle”. According to Peter himself the principle goes like this: “In a hierarchy every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence”.

While the book Peter wrote in 1969 was a satire rather than solid evidence, a recent study published in Harvard Business Review showed that, sadly, in today’s workplaces the Peter Principle is very much alive.

The Peter Principle

Let’s first explain the Peter Principle in more detail.

Imagine you work as a sales employee in an organization. You’re doing a really good job and you’re hitting all your targets. Your high performance is noticed. You are rewarded with a promotion to a senior sales role. In this role you do well again, so you get another promotion.

Now, you are a sales manager. Your new job is quite different. You’re not making sales—the thing you are so good at. Now you’re suddenly expected to manage salespeople. In this new job you figure out that managing people is quite a different ballgame, and not something you’re particularly good at.

All of a sudden your rapid climb up the corporate ladder grinds to a painful, stressful halt. If your current performance is not deserving of a promotion, you are stuck in a position that demands more than you can give. You’ve reached your “level of incompetence”.

Laurence J. Peter: “Look around you where you work, and pick out the people who have reached their level of incompetence. You will see that in every hierarchy the cream rises until it sours.”

You see what happens? The organization loses a good salesperson and gains a bad manager. A person is promoted to their level of incompetence: a clear lose-lose situation.

As painful as this might sound (for both the individual and the organization!), it happens all too often in today’s workplaces. What Peter vividly discussed in his 1969 book was recently researched by three professors from Yale, MIT, and the University of Minnesota.

Study

Alan Benson, Danielle Li, and Kelly Shue studied 214 firms in the US and analyzed the performance of their sales forces from 2005 to 2011. In the study were a total of 6,515 managers, 53,035 subordinates. A total of 1,531 promotions were researched.

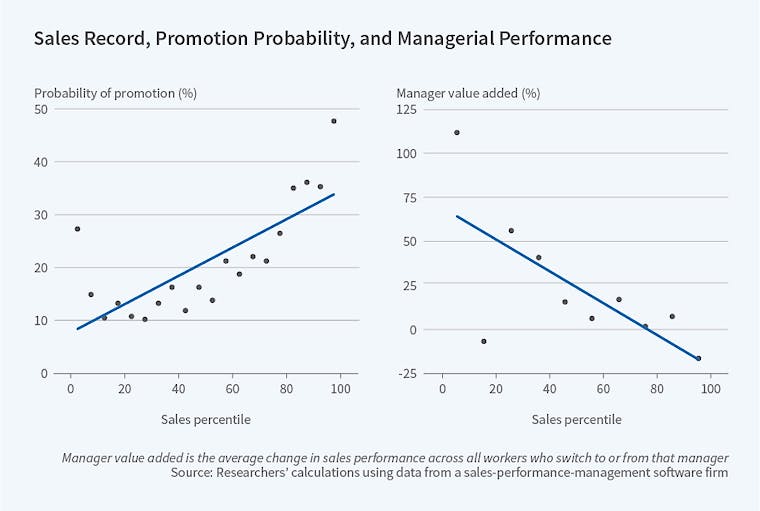

The image below shows the outcomes of the study.

The image on the left clearly shows a correlation between sales performance and the chance to get promoted into a management function. At the same time the image on the right shows that sales performance is negatively correlated with the performance as a sales manager.

Join us to explore these transformative insights and unlock the first chapter of our book, on the house! GET YOUR FREE CHAPTER NOW!

The conclusion from their study? A quote from the authors says it all: “In our data […] better salespeople ended up being worse managers.” The study clearly indicates the Peter Principle is very much alive. The big question is: how to overcome it?

Defying the Peter Principle

Contrary to most traditional organizations, many progressive organizations we’ve visited over the past 2.5 years have found ways to defy the Peter Principle.

They have put in place radically different structures to make sure they don’t end up with an organization filled with people at their level of incompetence. Here are some of these structures.

1. Change promotion criteria

The Peter Principle is alive because promotions are mostly based on an employee’s current performance. This doesn’t make any sense as the research clearly shows: there’s a negative correlation between current job performance and the added value of that person as a manager.

Progressive organizations therefore change the promotion criteria. They focus on assessing other characteristics of candidates that are better predictors of managerial success.

Characteristics such as collaboration experience, leadership traits, emotional intelligence and communication skills are much better predictors, and therefore much more valuable in predicting who will add the most value as a manager.

2. Evaluate your manager

To fight the Peter Principle, it is important to understand where in the organization there’s poor leadership. Strangely, many traditional organizations seem to think the best way to judge a manager’s leadership is by asking the boss of that manager.

But wouldn’t it make much more sense to ask the people who are led by the manager to assess leadership potential? Many progressive organizations certainly think so.

They abolish top-down performance evaluations and replace them with bottom-up evaluations. And let’s be clear, we’re not talking about those 360 feedback forms that you fill out and never hear of again.

We’re talking about proper bottom-up evaluations of managers that are openly discussed within the team before taking necessary actions.

Bucket List company UKTV introduced bottom-up evaluations to ensure “zero tolerance for bad leadership”. They even made all these performance evaluations transparent to the employees.

CEO Darren Childs: “In order to fight bad leadership, we need to know if and where there is bad leadership. Once we know it, we can do something about it. We can either train these people to become better leaders, or they can be put in a position that better fits their talents. This is how we work on our zero tolerance for bad leadership.”

3. Select your manager

Some take it even further: they let employees select their managers. Swiss IT company Haufe Umantis, for example, democratically elects all its leadership positions on a yearly basis (all the way up to the CEO).

But also manufacturing companies like FAVI and Haier let employees select their own leaders to make sure they are good leaders, not just great specialists who were promoted from the top.

4. Multiple career paths

Another common sense, but little practiced, approach to defy the Peter Principle is to create multiple career paths. Where in traditional organizations the only way to get promoted is to move into a management position, in progressive organizations you can get promoted in other directions too.

For example, if you’re a damn good IT Developer you don’t necessarily have to move into a management position to “get a promotion”. With multiple career paths, you can ‘move up the ladder’ on a technical track that allows you to develop your skills and talents.

Importantly, reward structures need to be aligned with this, allowing specialists to get the rewards and status they deserve without having to become a manager.

Multiple career paths are offered by companies like Spotify and Happy Ltd to prevent the rise of mass incompetency in their organizations.