The Self-Management Hype: Aren't We Just Reinventing The Wheel?

We read a lot about the rise of self-managing teams in contemporary organizations. Although the label, self-managing teams, has gained traction in recent management literature, it is by no means a novel phenomenon.

Recently we made a deep dive into academic research on self-managing teams. (One of us started a PhD on the subject.) To our surprise, we tracked the idea back to 1941. What we found shows the concept of self-managing teams is really nothing new.

The academic roots

Almost from the birth of modern organization studies, researchers have argued for a more decentralized and democratic approach. Even in the 1940s, theorists suggested alternatives to ‘bureaucracy’s confining routines and rules.’

The academic roots, and empirical evidence of, self-managing teams can be traced to the 1950s when British scientist, Eric Trist, reported on self-regulating coal miners in his now famous article, ‘Some Social and Psychological Consequences of the Longwall Method of Coal Getting.’

Subsequently, Trist’s work was built upon. Examples include Scandinavian experience with semi-autonomous teams in the 1970s, self-managing teams at the American Gaines Dog Food plant in the 1980s, and self-managing organizations like Morning Star, Zappos, Valve, FAVI, Haier Handelsbanken, and Buurtzorg in more recent publications.

In older academic papers, researchers advocate that ‘organizations must radically change their managerial structure by converting to worker-run teams and thereby eliminate unneeded supervisors and other bureaucratic staff.’ This particular statement originates from Professor James Barker’s 1993 article ‘Tightening the Iron Cage, concertive control in self-managing teams'. Although published more than two decades ago, the statement sounds suspiciously like advice from the top-notch management gurus of today, right?

If we delve further into Barker’s landmark article, he makes the case even stronger: ‘workers in a self-managing team will experience day-to-day work life in vastly different ways than workers in a traditional management system. Instead of being told what to do by a supervisor, self-managing workers must gather and synthesize information, act on it, and take collective responsibility for those actions.’

Revival of an old concept

As illustrated by Barker, the rise of self-managing teams in management literature could be better described as the revival of ancient self-managing team concepts.

Other familiar concepts described by Barker that would fit modern day management literature like a glove.

On structure

‘Self-managing team workers generally are organized into teams of 10 to 15 people who take on the responsibilities of their former supervisors. The team’s members are cross-trained to perform any task the work requires and also have the authority and responsibility to make the essential decisions necessary to complete the function’.

On function

‘Usually, a self-managing team is responsible for completing a specific, well-defined job-function, whether in production or service industries. Along with performing their work functions, members set their own work schedules, order the materials they need, and do the necessary coordination with other groups.’

On leadership

‘Top management often provides a value-based corporate vision that team members use to infer parameters and premises (norms and rules) that guide their day-to-day actions. Guided by the company’s vision, the self-managing team members direct their own work and coordinate with other areas of the company.’

On outcome

‘Besides freeing itself from some of the shackles of bureaucracy and saving the cost of low-level managers, the self-managing company also gains increased employee motivation, productivity, and commitment. The employees, in turn, become committed to the organization and its success.’

These claims sound even more modern-day when the author argues ‘that self-managing teams make companies more productive and competitive by letting workers manage themselves in small, responsive, highly committed, and highly productive groups.’

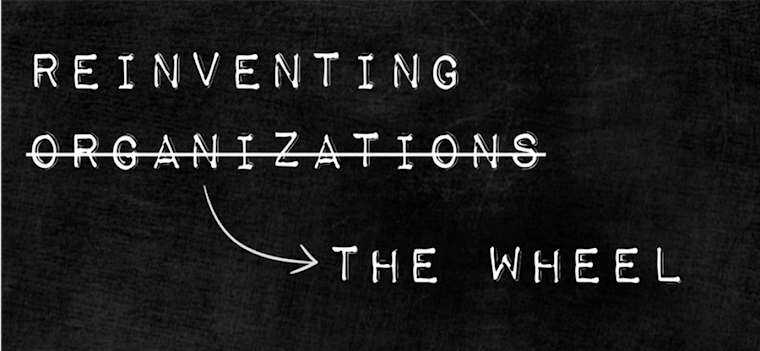

Reinventing ~~organizations~~ the wheel

Subsequently, the push for flatter organization structures became something of an obsession in the 1980s and 1990s business literature. Academic researchers, together with influential business consultants like Peter Drucker and Tom Peters, urged their readers to start de-bureaucratizing their firms.

Some three decades ago, those scholars unleashed a flood of literature announcing the approaching doom of bureaucracy and hierarchy. All of them proposed more human-centered organization designs, built on agile structures and practices.

Their central argument? ‘By cutting out bureaucracy and rules, organizations can flatten hierarchies, cut costs, boost productivity, and increase the speed with which they respond to the changing business world.’

The topic then seemed to vanish from academic interest for many years, only to be picked up again more recently by a new generation of gurus styling it as a ‘novel and exotic phenomenon’.

Calling self-managing teams a novel phenomenon is utter nonsense, as we have shown this concept is firmly grounded in academic literature.

What seems to have changed, however, is that the concept is now actually being ‘practiced’ more visibly, and with more mainstream traction. It is something we happily witness more and more in the Bucket List companies we have visited.

Nevertheless, it should be clear by now that many contemporary self-managing organizations are not only reinventing their organization, they are just as much reinventing the wheel.